-

| July, 16, 20201 Billion People Live in Informal Settlements Worldwide: Here are Seven Key Challenges They’re Facing During COVID-19

Read More -

| June, 05, 2020Impact is the new mainstream – Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group writes for IDR Online

Read More -

Business Standard

| February, 24, 2020Aavishkaar Group featured in Business Standard in an exclusive story as part of ‘Lunch with BS’ tilted’ Early mover advantage’

Read More -

Next Billion Series

| January, 21, 2020Women Feeding Africa: Innovative Business Solutions to Close the Gender Gap in Agricultural Productivity

Read More -

Textile

| January, 10, 2020Setting goals for future : Business India covers Aavishkaar Group and Intellecap’s pioneering foray in Circular Apparel with CAIF

Read More -

The Hindu Business Line

| December, 10, 2019The tough task of drawing up a structure and norms for a social stock exchange

Read More -

Forbes India

| November, 08, 2019A ‘Phygital’ model to enable rural banking: Intellecap writes for Forbes India

Read More -

Business Standard

| October, 14, 2019Aavishkaar Group to catapult into Asia, Africa with latest capital infusion

Read More - Cash income is the primary reason for account dormancy and rural cash economy. By digitising the income for the farmers, as well as their business expenses, FIs can look to drive account primacy, which in turn encourages banking behaviour. Partnerships with aggregators such as FPOs, co-operatives etc. or digital agri platforms can facilitate the effort.

- Liquidity of the digital money earned, through trusted entities, is vital to build a sustainable solution. On-boarding trusted value chain players as BCs can drive liquidity of the digital money and allow people to transact frequently. Through this, savings also get a much needed push and travelling to a physical branch is no longer required. Cash can be withdrawn in bite sizes, while the rest is saved automatically. Innovative goal oriented ‘gold savings’ or ‘Diwali savings’ products that leverage local customs and aspirations of rural consumers, can further promote digital savings.

- Phygitisation of the kirana value chain through FMCG/OEM partnerships and enabling digital payments at the merchants, through USSD or a merchant assisted model, can help complete the digital loop, and also enable access to credit for merchants. Retailers can also double up as BCs, adding to their existing incomes. The digital trail capacitates working capital (WC) finance to retailers, thereby improving SKU holding power and turnover.

- The phygital ecosystem data trail can enable access to finance for all key stakeholders. Products such as cattle finance, WC finance and equipment finance can be offered through data-driven scorecard tools created by the banking / MFI players, leading the value chain digitisation effort. Partnership with equipment OEMs can also drive loans against the (semi- perfect) collateral by enabling interest subvention and promoting secondary market for collateral under a buy-back agreement.

1 Billion People Live in Informal Settlements Worldwide: Here are Seven Key Challenges They’re Facing During COVID-19

1 Billion People Live in Informal Settlements Worldwide: Here are Seven Key Challenges They’re Facing During COVID-19 : The article in Next Billion by Margaret Nakunza, Associate, Intellecap Africa was based on the AVPA and Sankalp Dialogues webinar series, which explores how the business and development sectors are responding to the pandemic.

AVPA, in partnership with Sankalp Dialogues, kicked off a webinar series in April, to find out what various organizations across the continent are doing to #CrushTheCurve .

The virtual convening is ongoing, and it aims to:

-Share examples of how program implementers are responding to the outbreak, ranging from preparedness to mitigation

-Hear from voices on the ground and discuss how best to address upcoming challenges and reduce their impact

-Share solutions that can be easily embraced and implemented effectively, efficiently and quickly

Impact is the new mainstream – Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group writes for IDR Online

Mumbai, June 4, 2020: COVID-19 has brought an end to the ‘greed is good’ era. There will now be a new economic world order in which the only thing that will matter is an inclusive and sustainable world.

Impact is the new mainstream says Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group as he writes for IDR Online

As the challenges of COVID-19 unravel and ravage humanity across the globe, one recurring discourse has been to use this disruption to reimagine the economic architecture. Is it possible to convert the pandemic into a launch pad for a more humane, inclusive, and sustainable world?

The idea of impact investing is one such powerful idea, conceived to challenge the hegemony of greed and the desire to maximise returns at all costs, by taming capital into a more humane, sustainable, and inclusive tool for change.

In my journey of two decades chasing this dream of making impact a real alternative to mainstream global capital pools, I have learnt that money is a complex subject. And because most global capital is regulated by government (but not controlled by it), I’ve also realised that it is nearly impossible to tame global capital’s natural instinct.

But the disruptions caused by COVID-19 give me hope that, despite these limitations, impact investing may have a major role to play over the next decade in reimagining a new world—a world with no hunger, no poverty, and no inequity.

Commercial capital is driven by greed

The global capital pool is roughly USD 300 trillion and its primary objective is to maximise returns within the boundaries of identified risks. Capital markets work on mandates, and so far, they have focused almost entirely on this single parameter—maximising returns.

Over time, there have been significant causes that have knocked on the doors of capital—from philanthropic asks to help the vulnerable and marginalised, to demands to balance the reward equation to avoid concentration of capital, to calls for stopping investment in extractive industries such as oil, mining, and fossil fuels. However, none of these appeals have influenced the mandate of capital in any significant manner.

“Some among the affluent try to make an impact through philanthropy, but the contribution pales against the destruction caused by the ‘greed is good’ approach.”

The disdain for these asks is not because of ignorance of the risks that arise from social inequity or climate change. It is because the leadership of capital markets probably believes that the giant machine of capital allocation has little to do with these asks. They believe that corporate social responsibility (CSR) and philanthropic activities is where these demands should be directed, since capital markets must focus on an unadulterated vision of return at all costs.

Not surprisingly, this leadership represents the privileged and powerful. While they accept in hushed tones the downsides of this approach for the poor and marginalised, they consider them as collateral damage to the holy quest for capital multiplication.

An equally important factor is that while the world of capital plans for long-term risk management, its incentives as a global collective are more aligned to quarter-on-quarter performance. Long-term-ism is a philosophy to pontificate, not to act. While those who are conscious among the affluent do try to make an impact using personal wealth through philanthropy, the contribution pales against the destruction being wheeled in by the mainstream ‘greed is good’ approach.

The idea of impact investing

Impact investing—an idea mooted at the turn of century in India and the USA—believes that one can do good to do well. The idea took some time to find a toehold in the world of capital—the early adopters and leaders were focused on demonstrating that making impact has powerful potential to deliver returns. One of the goals of impact investing was also to wean away large pools of commercial capital from its single minded pursuit on maximising return, and instead deploy it to build businesses that were inclusive, sustainable, and impactful, while delivering returns.

During its early days, the idea was seen as utopian, and marginalised as a fringe innovation, as an alternate to philanthropy, rather than a challenge to the hegemony of commercial capital and its bottom-line pursuit. This has changed over the last decade. Today, with USD 500 billion allocated to impact investment, some of the largest aggregators of capital are now committed to this idea and see it as an important tool of change.

As one of the early messengers, I have often wondered if commercial capital has simply co-opted the idea of impact investing to make sure it does not challenge the capital hegemony, by taking away the focus from its true potential. Because, while it has pushed people towards measuring the outcomes of their investment, it has not changed the key architecture of how capital is deployed.

Mainstreaming impact investing

Impact investing has the potential to disrupt the global economic order and threaten the established and deeply entrenched world order. And the best way to neutralise a great idea and to preserve the status quo, is to co-opt the idea and mainstream it. Impact investing as an idea is therefore being co-opted by the capital aggregators, so that in the guise of numbers and outcomes, its soul can be trampled.

“Today, the language of the impact investing is no different from the language of mainstream capital.”

The idea of ‘doing good to do well’ is being replaced by ‘doing good and doing well’, thereby separating the impact from the process of capital allocation. This allows for minor tweaks in the current economic architecture and lets us continue to do what the capital world has done for ages, and be seen as impactful and sustainable.

As we stand today, most people who entered impact investing believe that it allows you to have your cake and eat it too. That it is possible to change the world while satisfying your greed. By co-opting the word impact, the idea of change has been diluted and compromised. Today, the language of the impact investing is no different from the language of mainstream capital.

COVID-19 offers us hope that things will change

To say that COVID-19 is a pandemic and a health hazard is obvious. But it is also a virus that has democratised fear, as it ruthlessly impacts everyone, including the rich and the powerful. Ministers, bureaucrats, CEOs, fund managers on one side, and nation states with powerful armies and some of the highest per-capita incomes on the other, have all found themselves tamed by the onslaught of a virus weighing just a few micrograms.

With the wheels of economies coming to a grinding halt, the managers of capital have seen a decimation of wealth as never before. It has hit those who never thought that such risks could manifest themselves and result in such destruction for them. Moreover, they have no idea as to how deep, long, and damaging this could be going forward.

‘Greed is good’ is dead

The privileged minority that controls the USD 300 trillion capital pool, which has always looked at risk and return as a continuum, is faced with an undefined risk that destroys value. It is not about maximising returns anymore, but protecting value. Can they protect the USD 300 trillion from losing its value? For the first time, it is not a question of earning less returns on the capital but actually losing it, and therefore, the focus is on the return of capital than return on capital.

COVID-19 has demonstrated to the money managers that risks that seemed like theoretical constructs by scientists, or showed up as glaciers melting in Antarctica, or rising sea levels in Southeast Asia, can strike and paralyse the global economy. The pandemic has brought the unsustainability of the outside world inside the boardroom of the rich and powerful. There is fear now.

Resilience trumps return

If greed is dead, what then is the new world order? It is one where resilience trumps return, where survival and sustainability of capital far outweighs the return that capital can generate. Given this, the best-case scenario for anyone is ‘resilience with return’, since ‘return at all costs’ is not an option anymore. This requires asset managers to take a long-term view of their actions on the society, before they take a view on the immediate return.

This is exactly what impact investing offers. It encourages the world of capital to embrace sustainable investing for good returns. It seeks capital to be invested in a way that uplifts people and society, sustainably.

Impact is the new mainstream

Given COVID-19 and its fallouts, mainstream capital now has to mimic impact investing and look, feel, and act like it is making impact, rather than the other way round.

In the new economic world order, the only thing that will matter is an inclusive and sustainable world. And when that happens, capital, companies, and leaders will look to build businesses that further equity, inclusiveness, and sustainability as a core strategy and seek shareholder returns that draw from this.

This new world order will also bring about other fundamental changes

First, capital will have to face a much higher level of accountability and scrutiny on the idea of impact, inclusion, and sustainability, and it may not be enough for a business to just claim impact. The idea of preparing a balance sheet and developing an accounting standard that takes into account the impact on sustainability will be pursued with same vigour over the next decade, as were accounting standards in the last century.

Second, we will require significant technological interventions, because impact investing by nature takes place in remote and inaccessible regions, where one can only work through technology. Digital transformation in the space of impact will be one of the most far-reaching tectonic shifts that we will see in the near future.

“The quest for resilience will force the world of capital to replace the idea of greed with sustainability, inclusion, and impact.”

Globally, we will also see a shift in geopolitics—from the hegemony of one or two, to several blocks of power. And even though it has become a cliché now, I think oil is a passé, and we will see investments in greener energy. Climate, energy, environment, and sustainability—these will become buzzwords of the future. There will be new roles for technology, new models of sharing, and new sectors—health, water and sanitation, hygiene, and so on—will lead the way capital is deployed.

Overall, the quest for resilience will force the world of capital to replace the idea of greed with sustainability, inclusion, and impact.

Change will come because it is about self-preservation for the rich

The world has seven billion people but very few control capital. And while 99.9 percent of humanity may forget the trauma of the COVID-19 crisis few years down the line, the few who control global wealth—those with the money and influence—are unlikely to forget the impact of this pandemic.

The world will change not because people will remember the trauma caused by the migrants walking; it will change because the virus has permeated the fear right inside the boardrooms of the largest companies, and the family offices of the richest people. The changes will come as self-preservation for the rich becomes a priority, and global shifts only take place when the powerful are fearful.

To read the full article in IDR Online Click Here

Mainstreaming gender lens capital solutions for women-led SMEs-

24th February, Mumbai: Economic Times Online recently featured an article on ‘Mainstreaming Gender lens capital solutions for women-led SMEs’ which was authored by Trina Roy, Associate, Intellecap.

The article largely talks about how Gender Lens Investing (GLI) as an approach to promote social and/or economic empowerment of women, in addition to financial returns has gained traction in the past years.

In the article Trina talks about how India currently has more than 8 million women-led businesses that represent 13.76 % of all businesses in the country as estimated in the Sixth Economic Census. With improved education outcomes, targeted interventions by the government and private sector, and other socio-economic factors; women entrepreneurship has indeed witnessed a rise over the last couple of years. States such Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal and Maharashtra have the highest share of women entrepreneurs.

Applying a gender lens to budgetary allocations, the government as an impetus to promote women led entrepreneurship has taken certain steps. These have included measures such as expanding the Women SHG interest subvention programme to all districts, making one woman in every SHG eligible for a loan up to 1 lakh under the MUDRA Scheme, among others.

According to the author, while these are welcome moves by the government to ease the access to finance challenge – an acute challenge faced by women entrepreneurs, the time is right to initiate conversation about bigger reforms.

She opines that, Gender Lens Investing (GLI), an approach to promote social and/or economic empowerment of women, in addition to financial returns has gained traction in the past years. Adopting the GLI approach, investors seek to channel debt and equity to businesses that create positive gender outcomes through various strategies. Some of these include supporting women as entrepreneurs, investing in development of products and services benefiting women, and channeling capital in businesses having a high share of women employees and in their value chains.

For India to unlock the potential of women entrepreneurship, concerted strategies to catalyze GLI and develop effective financing products for MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) in particular will be critical. In this article we explore how the GLI philosophy is applied to supporting women entrepreneurs, specifically in the SME sector.

Elaborating on it further, she says that supporting women led SMES through targeted demand driven financing approaches and products lies at the heart of transforming the capital access scenario for women entrepreneurs in India. Depending on the type of scale and sector of an enterprise, multiple approaches can be explored.

First, after assessing the sector and sub sector category of MSMEs, tailored financing products combined with capacity building support can be developed. Majority of women led enterprises being subsistence businesses do not typically attract capital from investors or banks. Many of these women-led SMEs in India operate in sectors such as textile and handicrafts, food processing, beauty and wellness and are overwhelmingly concentrated in the micro and small scale business segment. Their particular needs are significantly different from high growth businesses to which the traditional start up ecosystem caters or steady businesses to which banks provide capital support. Bearing in mind their business models and market needs, sector or cluster specific financing products that provide patient capital aligned to growth rates and pay back periods would be instrumental to spur growth.

Second, blended financing products combining different types of capital – debt, equity and grant can also support women-led SMEs in underserved geographies or in sectors with low profit margins. With flexible capital, blended financing products reduce capital costs and can be leveraged effectively to overcome the problem of low returns and high risks; concerns that often limit traditional private sector investments. As an investment structure mixing concessionary and for-profit capital, the Women Entrepreneurs Opportunity Facility (WEOF) is a remarkable example of an effective blended finance product deploying capital to a segment often overlooked by financial institutions and global investors.

Third, innovative structuring of gender financing through development impact bonds, guarantee bonds, soft loans can also be explored to meet the needs of women entrepreneurs in the MSME sector. These serve as effective mediums to bridge social goals and economic returns. Experiments with development impact bonds and outcome bonds are at its nascent stages and have been promising in areas like health and education in India presently.

How would the DIB work? Here she suggests that adapting similar structuring to create a gender focused impact bond would channel private capital toward women entrepreneurship and augment the Government of India’s efforts to promote it. DIBs bring together the public, private and philanthropic sectors and align their interests towards a common set of objectives. Commercial investors pump in capital in a DIB, and the DIB in turn on-lends growth capital at low interest rates to a target women-led SME segment. Over the agreed tenure period, women-led SME repay back the capital with the given interest to the DIB. An independent agency monitors the outcome in terms of scale achieved by the SMEs and on its basis, a donor(s) and/or the government makes a payment to the DIB. Commercial investors are paid back by the DIB using the capital repayment by SMEs and the outcome based payments from the donors or government.

Other experiments including guarantee fund, soft loans, and interest rate subventions are viable alternatives to consider as well. To bring about a paradigm shift, efforts to build capacity and ease capital access must work simultaneously. Serious efforts by both the government and private sector are necessary to steer and mainstream Gender Lens Investing for women entrepreneurs in India.

In her conclusion she says that going forward, building a strong evidence case for GLI will be an imperative first step. Supporting data-backed research to provide insight into the performance and potential of such SMEs is crucial. Additionally, mapping stakeholders like investors, incubators, experts, enterprises, to identify opportunities of collaboration will strengthen its case. The current measures targeted towards women in SMEs provides the initial boost and is a larger signal for other ecosystem players, specifically the private sector to come forward and build on this momentum.

Aavishkaar Group featured in Business Standard in an exclusive story as part of ‘Lunch with BS’ tilted’ Early mover advantage’

Saturday 22nd February , Mumbai: Aavishkaar Group was recently featured in Business Standard in a story tilted ‘ Early mover advantage’ when Vineet Rai Founder and Chairman in an exclusive interview with Anjuli Bharagava as part of ‘Lunch with BS’ spoke about how high risk appetite combined with strong survival instinct is the recipe for success.

The entire interview with Business Standard :

In the early 2000s, when the world was yet to wake up to the promise of impact investing, Vineet Rai was registering a firm with the princely sum of Rs.5,00O to raise funds to transform rural India. The following year, he borrowed a lakh from his wife and registered an advisory com¬pany to help new entrepreneurs. Around the same time, in the United States, Jacqueline Novogratz set up Acumen, first as a fund and which later became a non¬profit. A year later, UK businessman turned philanthropist Sir Ronald Cohen set up Bridges Fund Management that in due course crystalised into an impact investing company.

That makes Aavishkaar group chairman Rai a pioneer in the impact investing space in India arid one of the early entrants globally. We are meeting for a long pending Dinner with BS at The Table in Mumbai’s Colaba area. Without wasting time we order a SoBo salad that we intend to share. Rai opts for shrimp tacos and a diet coke and I order a roasted almond tortellini. The term “impact investing”, he explains, was coined many years later —at a meeting at Lake Como, Italy, in 2008 by 10 members of the impact community. Would he then qualify as the “father of Impact investing” in India like his mentor Basix’s Vijay Mahajan, who is ofetn called the father of micro-finance? He laughs off the suggestion, adding that would be too laudatory.

Rai was 29 when the idea that a blend of talent and high risk capital could trans¬form rural India gripped him. He present¬ed his idea before the board of the Gujarat government non-profit he was CEO of only to be told that venture capital was barely available in Indian cities, let alone raising such capital for rural India.

Meanwhile, a small group of Indians based in Singapore had heard of Rai and sent him a ticket to visit them (Rai couldn’t afford the tickets for what would be his first-ever visit outside of India). They hosted a dinner of SO local Indians, sat through his presentation and a bunch of them committed some money to his plans, not expecting to get it back.

A bull in a china shop and keen to prove his theory, Rai returned to India, quit his job — to his wife’s horror — and set the ball rolling. He had earlier helped Vikram Akula in building SKS Microfinance as a friend and consultant and had become quite familiar with the micro-finance landscape in India. But the going wasn’t easy for Aavishkaar in its early days and by end-2003, Rai was struggling to keep his head above water. That’s when Mahajan pointed out that Rai was in a unique position — he knew more about micro finance than most people in the equity space did and he knew more about equity than most in the micro-finance space did. So why doesn’t he just marry the two?

He followed the advise and worked “30 hours out of 24” with his small team of equally committed people. At that time, Intellecap was assisting two billionaire Kiwi brothers, Richard and Christopher Chandler, find the right opportunity to invest in India’s micro-finance industry. Impressed with his handling of the deal, the brothers offered to pick up a majority stake in Rai’s business. Rai refused. “At the time, Intellecap had Rs. 1 crore in spare cash and I thought I was the richest man in the world,” he says. That apart, he also knew there were no free lunches and was scepti¬cal of the strings that might be attached. The Chandler brothers were not accus¬tomed to taking a “no” for an answer and persuaded Rai to sell 40 per cent in Intellecap for $8million. The year was 2007.

Our dinner is over and Rai orders a cap¬puccino. We are by now in 2011 and the pressure on Rai to find a way to return the money invested by the Chandlers was building up. So he took another mad gam¬ble, against the advice of all. He went ahead and created Intellegrow (an NBFC) and bought Arohan, a micro-finance com¬pany, which he got cheap at the peak of the micro-finance industry crisis.

As they say, fortune favors the brave. The Aavishkaar fund became one of the first investors in several early stage, highly successful MFIs of the day including Equitas, Basix and Utkarsh. Arohan grew by leaps and bounds and is the fifth largest MFI in India today.

Rai starts talking about a mind-blow¬ingly complex restructuring of the group that I tune out of and by the time I catch him again the holding company Aavishkaar Group has been born. The group sold stake in the holding company twice, raising over $100 million in two years (part of the money was used to buy back stake from the Chandlers), taking Rai and his associates’ share in the group down to just over Si per cent.

I interrupt to point out that many in the impact space have questioned his decision to venture into Africa and South East Asia, arguing that he’s bitten off more than he can chew. “Can we go wrong? Yes, we can. But if I don’t take risks, we die,” argues Rai.

If some describe Rai as a risk-taker, others say he is ambitious. The group today has Rs.8,O00 crore in assets under management, and by 2025, he aims to be well entrenched in the international market, with assets under management to the tune of Rs.50,0O0 crore. He’s also under pressure again to create exit options for his present set of investors.

I switch to a broader debate: Over the years, there has been criticism globally that the impact sector is seeking to take a moral —high ground and make other businesses appear soul—less. This lot argues that every business will have some impact and that the impact community comprises wolves in sheepskin. So does he see himself as a messiah for India’s poor? Rai holds no grand illusions. The impact sector isn’t really a “Florence Nightingale” and can— not solve the more complex problems that society faces. “If a child is dying of starvation or a baby girl is killed, what can I do?” he asks. He can only solve problems that lend themselves to a viable business model. Also, he’s in it because this is what he likes doing, not because he can “change the world”.

That more or less confirms my assessment of Rai —that he is grounded. He lives in Mumbai’s west¬ern suburb of Kandivali although lie can easily afford a fancier address iii the city. I also see him asking his driver to call it a day even before we finish dinner because he is concerned it might be too late for him to find trans¬port to get home.

We have been talking over three hours now. As we wind up, I tell him that he appears to be enjoying the perpetual— pressure-cooker work environment. “An entrepreneur should always remain under pressure or he will die,” he says simply. He just hopes many more are left better off at the end of this over—wrought journey.

Women Feeding Africa: Innovative Business Solutions to Close the Gender Gap in Agricultural Productivity

Women make essential contribution to the development of agriculture and rural economies in emerging countries. On average, women make up 43% of the agricultural labor force in developing countries, ranging from 20% in Latin America to 50% in Eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Further, in SSA women contribute 60-80% of the region’s food. Yet despite their importance to the sector, women continue to face specific constraints that limit their productivity. They have lower access to agricultural inputs and farming knowledge, earn lower returns on the inputs used, and face gender-based distortions in the product markets. Similarly, women are also disadvantaged by other gendered norms and practices, which result in fairly rigid and unequal divisions of labor both at the household level and the marketplace. Women’s participation in the sector is thus limited to value chain nodes and crops with lower economic return than men. The resulting gender gaps in agricultural productivity can be substantial, ranging from 13% in Uganda and 16% in Tanzania, to 28% in Malawi.

So what would happen if we closed the gender gap in the sector and women accessed the same productivity resources as men? Research shows that yields could increase by 20-30%. In Rwanda for instance, closing the agricultural gender gap would lead to about a 19% increase in crop production, which would add $419 million to the country’s GDP. Closing the gap could bring 180 million Africans out of hunger, and lift millions of families and communities out of poverty. As such, innovative solutions to the constraints facing women need to be explored. Below, we discuss a number of initiatives that are developing ground-breaking solutions to support the region’s female farmers.

ENHANCING ACCESS TO CREDIT FOR WOMEN IN AGRICULTURE

Women’s access to inputs – fertilizers, pesticides, hybrid seed, wage labour and machinery – is highly influenced by access to credit. But on a general level, the agricultural sector is considered high-risk for most traditional lenders; lending to the sector is thus highly collateralized and follows stringent underwriting processes. Despite the importance of the sector, lending has remained relatively low at only 2.4%, 3.6% and 3.7% of total loan portfolios in Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria, respectively. And this number is significantly less for women, due to their limited ownership of assets and land used as collateral, and to the lack of banking and credit data about female borrowers (only 27% of women in sub-Saharan Africa were estimated to have a financial institution account in 2017). In addition, financial decision-making powers in some countries continue to lie with men as a result of gender-biased and retrogressive regulations and women’s low literacy levels.

Nevertheless, women do undertake various transactions, creating data points that can be leveraged to generate credit scores. To that end, a number of players are already working to digitize women’s transactions. The Aga Khan Foundation, for example, has been working to digitize the operations of women savings groups in Tanzania. TruTrade purchases produce from women farmers in Kenya and Uganda and pays them directly through their mobile phones, which not only helps build a digital profile but also gives them security and control over their finances.

Some companies are even developing financial products customized for women. For example, Cherehani Africa is targeting rural women in Kenya through their “Kilimo (Swahili for agriculture) loans,” which provide subsidized credit to finance high-yield seeds, pesticides, green house kits, high-breed dairy cattle, fisheries and poultry. The company also connects farmers to input suppliers through their online platform.

OPTIMIZING WOMEN FARMERS’ AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

Across the agricultural value chain, production is one of the most female-driven stages. However, women not only face the challenge of unequal access to a variety of productive inputs – fertilizer, seed, contemporary farm implements and paid labour – but also achieve unequal returns on those inputs, which limits their output. To help address this, Agrinfo, a female-led aerial drone surveillance enterprise in Tanzania, is working with women in the country to identify their crop cultivation needs and provide solutions that will reduce pest infestation and diseases.

FACILITATING GENDER-RESPONSIVE EXTENSION SERVICES

Knowledge and training in farming techniques is also key to enhancing the productivity of the inputs used – and ultimately boosting the efficiency of the broader sector. Yet women farmers receive less than 10% of agriculture extension services, limiting their ability to apply good agronomic practices – and low literacy levels are considered a major barrier to their use of these services. There are several innovative approaches that aim to address this, however. For instance, Digital Green uses a video-based approach to deliver extension services to women in India and Ethiopia; and the Talking Book audio device (established through a partnership between Amplio, the Mennonite Economic Development Associates and Literacy Bridge Ghana) is enhancing the delivery of practical and easy-to-learn extension services in Ghana.

INCREASING POST-HARVEST VALUE FOR WOMEN FARMERS

Sub-Saharan Africa loses about 30-50% of its total agricultural produce post-harvest, due to poor storage and transportation techniques. In many parts of the continent, women play a significant role in post-harvest activities such as drying, storing, cleaning and processing food. However, efforts to reduce post-harvest losses have tended to focus on technological solutions that women may not have the opportunity or resources to utilize. In response, Claphijo Enterprises in Tanzania is helping women make use of surplus or unsold mangoes by providing cheap communal drying and dehydration facilities. In addition, some of this dried produce is bought from the women and sold under the company’s brand, “Mama’s Flavors.”

CREATING MARKET AND VALUE CHAIN LINKAGES

Agricultural commodity trading has traditionally been male-dominated, with factors such as limited freedom of movement, and low access to infrastructure and information networks preventing women from participating in the marketing of produce, both locally and internationally. Women thus often rely on either their husbands or middlemen, who collect produce from their farms. Further, social norms require women to meet household food needs first before selling the surplus. And women also typically receive lower returns on their produce, because of gender biases in the product markets. All of these factors make it difficult for women to professionalize their farming work. To address these challenges, TruTrade provides information on prices and markets to women farmers in Kenya and Uganda, and directly links them to the buyers. GROOTS Kenya is also providing capacity building for women in Kenya, to help them exploit various market opportunities.

Though the solutions discussed above are exciting, for any sector to thrive, this sort of strengthening should be done at an ecosystem level – including both women farmers and development organizations. That’s the focus of organizations like African Women in Agricultural Research and Development (AWARD), whose Gender in Agribusiness Investments programme incubates innovations and enterprises built with the intention of helping to bridge the gender gap in African agriculture. It’s encouraging to see the emergence of these – and other – innovative organizations focused on supporting women farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Their work promises to have a major impact on the continent.

Setting goals for future : Business India covers Aavishkaar Group and Intellecap’s pioneering foray in Circular Apparel with CAIF

Out on the stands now*

Arbind Gupta from Business India attended the 11th Sankalp Global Summit 2019 and covered the pioneering foray in Circular Apparel with Intellecap’s Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF).

The 2 page detailed story in Business India Jan 2020 Issue, now out on the stands, captures a detailed overview on the textile industry with respect to the challenges and the need for sustainable fashion as a practice, capturing the launch of the 1st CAIF conclave, views and opinions from key spokesperson like Group Founder Vineet Rai, Intellecap CAIF Director Stephanie Bauer, Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail’s MD Ashish Dikshit and Chief Sustainability Officer Dr. Naresh Tyagi and the designers present during the summit

|

|

The textile and apparel industry is currently passing through a phase where it is finding itself in a quandary as it struggles to find a balance between its mainstream targets of productivity and production and sustainability goals. the current linear system of production, distribution and usage of t&a is not sustainable as there is little regard for environment impact. as a result, the industry is the second-greatest polluter globally.

Over 20 per cent of industrial water pollution is due to garment manufacturing. globally, 80 per cent of textile waste generated is not recycled and often sent to landfills or incinerated. in fact, the industry is responsible for over eight per cent of global pollution. with the growing economy and changing demographics, the consumption of textiles and clothing has gone up by more than 60 per cent today as compared to that in 2000 and this has significantly aggravated the whole situation. in the past 15 years, textile production has almost doubled.

Experts are of the view that the current take-make-dispose approach does not only adversely impact the environment and society, but also the future business of the t&a industry. while there are a few sporadic interventions across the value chain in order to address the issues and make the value chain more sustainable, a concerted effort is missing.

To address these issues in a more holistic manner as also set goals and achieve them in a time-bound manner, an industry-led platform – Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) – has been put in place recently in India. started in 2018 and formally launched in November 2019 at Sankalp Forum’s 11th Global Forum in Mumbai, CAIF is an initiative of Intellecap (an advisory arm of the Aavishkaar Group) in partnership with Aditya Birla Fashion & Retail and the Doen foundation, a dutch foundation supporting initiatives in the field of culture and cohesion and in the field of a green and inclusive economy.

“We at the Aavishkaar group pioneered the idea of impact driven sustainable investing in India, Africa, and South-east asia. as we look at the textile sector, and specially the apparel sector from the lens of circular economy and sustainability, we see the need for innovative ideas and start-ups to nurture these innovators, we need a flourishing ecosystem in addition to capital. through Intellecap and CAIF, we hope to contribute to this process and see transformation sweeping through the indian apparel industry,” says Vineet Rai, Founder of Aavishkaar Group, which is one of the world’s largest impact investors, currently managing assets worth about $1 billion, across India, Africa and Southeast Asia.

The Aavishkaar group was founded in 2002 with just $100 and with a vision to catalyse development in India’s under-served regions. it identifies capable entrepreneurs, provides them with capital, supplements it with a nurturing environment and helps build sustainable enterprises. with over 5,000 employees in India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Kenya and USA, the Group’s financial ecosystems include equity funds, venture debt vehicle, microfinance and advisory business including investment banking.

“At CAIF, our mission is to build capabilities and the ecosystem needed to create a circular t&a industry. we are building the ecosystem in order to search, seed, support and scale up circular innovations in India. we look to leverage the Aavishkaar Group’s approach of creating impact at scale through providing access to capital, knowledge, networks throughout an inventor’s journey,” says Stefanie Bauer, Director, Intellecap CAIF.

Says Ashish Dikshit, Managing Director, Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail ltd (ABFRL), “We are pleased to partner with Intellecap to accelerate the sustainable fashion concept through CAIF and build an industry level platform for a circular textile ecosystem. we intend to bring forth ideas and innovations to add more strength to our pioneering work around sustainability. the association with Intellecap will help us create, collaborate and mainstream the conversation around the circular economy and sustainable fashion“.

Dr. Naresh Tyagi, Chief Sustainability Officer, ABFRL believes that fragmented efforts so far have not yielded much result and there is a need to bring all these on a single platform like CAIF so that a coordinated and cohesive effort can be carried out towards building a conducive ecosystem for creating a circular industry. “The textile industry has been a laggard so far and now there is a need to catch up and join other industries towards building a strong base for creating a formidable circular t&a sector in the country,” adds Tyagi.

CAIF will leverage its digital ecosystem to ease discovery, drive innovations, and collaboration and support partners in identifying opportunities. the platform has formulated a roadmap that will guide one to the goals and targets it intend to achieve.

Currently, only one per cent of the material used to produce clothing is recycled. going forward, caif members will make significant efforts to source sustainably, use alternative and recycled material. concerted efforts will be made to bring down the level of hazardous chemicals, materials and harmful substances. caif members will also make considerable effort to reduce textile waste and eliminate single use plastics. Besides, there will be attempts to use renewable material in the production process.

In the past one year CAIF has generated an encouraging response from over 500 stakeholders that include textile manufacturers, retailers and brands, government agencies and multilaterals, enablers, entrepreneurs and innovators as also experts and academia. reliance industries, aditya Birla retail and fashion, h&m, raymond, landmark group, arvind and welspun are among the manufacturers/brands, while unido, world Bank, undp and nabard are among the government and global agencies who have extended their support to this platform.

Enablers include the international apparel federation, doen foundation, fashion for good, Beyond capital fund, sustainable earth foundation, c&a foundation and circle economy, whereas infini chains, trust trace, boheco, graviky labs, re:newcell, fibrelabs, dimpora, indidye, Kiabza, style lend and fairtrunk are among the enablers who have joined the caif initiative. imperial college london, national institute of design, sasmira, national institute of fashion technology and ‘good on you’ represent the experts and academia community.

Dealing with textile waste is one of the major challenges faced by the industry at present and calls for concerted efforts on the part of producers as well as consumers. as per an estimate, the clothing industry creates upwards of 150 billion pieces of clothing each year and close to 15 per cent of fabric ends up on cutting floors during production leading to wastage even during this phase.

Today, we consume 60 per cent more clothing than we did just a few decades ago, with average lifecycles of 3-6 months for a new garment. while consumption is increasing due to increase in purchasing power and decrease in prices, unchecked consumption contributes to the creation of close to 39 million tonnes of postconsumer waste each year. and only one per cent of the material used to produce textile & clothing is recycled across the globe and put back into the system. upwards of 70 per cent of all discarded clothing is sent to landfills, of which nearly 95 per cent can be recycled.

It has been observed that innovations exist to extend and shift the end-ofuse of a garment or a piece of fabric but they are often not available at scale and face challenges with blended fabrics. another big challenge faced is how we can strengthen the industry’s risk management and consumer engagement through increased supply chain traceability. “The fragmented nature of the supply chain, the current lack of information across the value chain, and changing consumer demand call for transparency solutions. in fact, 50 per cent of 150 brands surveyed recently have no visibility of their chain beyond Tier I ,” adds Bauer.

The recent transparency index published by fashion revolution indicates that a review of 200 major brands and retailers’ public disclosures gave companies an average of 21 per cent for the transparency of their supply chain. only two per cent of the 250 brands surveyed scored higher than 60 per cent on the transparency index. on the other hand, today, over 51 per cent of consumers are beginning to demand transparency and sustainability related product information. experts believe that while transparency is important, the fragmented nature of the supply chain also demands greater control through traceability and data management. Blockchain has started to transform the way information flows across supply chains due to the unique ability to create a physical-digital link between goods and their digital identities. this offers opportunities for a more transparent supply chain. all said and done, there is a strong belief that transition towards a circular economy will require a new level of collaboration and alignment. and moreover, there will be a need for concrete collaborative commitments on the part of the industry to make the entire initiative a success story.

The tough task of drawing up a structure and norms for a social stock exchange

Social enterprises may have to balance between improving the lives of people and earning returns

How do you define a social enterprise? The traditional way of looking at it has been that any venture that positively impacts the under-served is a social enterprise. But then issues arise as quite a few commercial enterprises too positively impact the under-served. Many of these enterprises raise money from committed impact investment firms, which do not always eye their investment from the prism of the return on equity they will get. They are more bothered about the impact that the firms create.

Open for Business

A social stock exchange is being blueprinted that will bring more money to NGOs and for-profit enterprises in development work Aavishkaar Group in conversation with Mumbai Mirror at the Sankalp Global Summit 2019

If you’ve always wanted to engage in some philanthropy but never knew whom to give to, or how, here’s the answer.

India may soon have a social stock exchange – a bourse for the social sector – where donors will be able to contribute to an NGO or a for-profit organisation of their choice that is ‘listed’ on the exchange. A 15-member working group, constituted under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi), which will regulate this social stock exchange, is currently putting together a blueprint for this. It is likely to submit its plans to both Sebi and the finance ministry for approval this month.

“Almost every Indian who has made money, wants to give back in some way or the other,” says Vineet Rai, founderchairman of the social enterprise Avishkaar, and a member of the working group. “The social stock exchange (SSE) would be a transparent and accountable way of doing this. The idea was proposed by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in the last Budget because there is a clear need for India to invest significantly more in its own development. Nonprofits have been doing good work for decades, but a new kind of ‘impact’ investing has led to the growth of forprofit social enterprises as well.” So based on guidelines drawn up by Sebi, both NGOs and forprofit organisations that operate in the social space can list themselves on the SSE. This will make it easier for potential donors to find and fund them; but it also brings a level of accountability to the work and finances of these organisations.

The working group, which was constituted in October, has been given the task of creating a framework that will help make the SSE a reality. It has had three meetings so far, and is now getting into the writing of the report, says Rai. Only five countries in the world — UK, Canada, Singapore, Brazil and South Africa – have anything like a social stock exchange. The working group plans to study them and perhaps borrow some best practises. The biggest benefit of the stock exchange is that it will bring more money to the development space.

A ‘Phygital’ model to enable rural banking: Intellecap writes for Forbes India

Aavishkaar Group’s content partnership with Forbes India, one of the most reputed business publication allows our leaders from across the Group to share their ideas, insights and expertise through this yearlong special series.

This is the eighth article as part of this partnership.

Mumbai, Nov 8, Friday: Neha Kumar, Senior Associate, Intellecap , Abhishek Shah, AVP, Intellecap and Himanshu Bansal, Former Associate Partner, Financial Services at Intellecap contributed the eighth story in the Forbes series November Issue as part of our yearlong content partnership with Forbes India.

As a quick recap the first story titled ‘Instant loans: Alternate data to drive next financial inclusion wave’ in this Forbes Series was authored by Atreya Rayaprolu, Co-Founder and CEO Tribe3. The second story titled ‘Smart villages: Driving development through entrepreneurship’ was coauthored by Santosh Kumar Singh, Director, Intellecap and Ankit Gupta, Manager, Intellecap. The third story titled ‘What most women-led enterprises in India have in common’ was coauthored by Urvashi Devidayal, Sankalp Lead India and Prachi Maheshwari, Gender Lead Intellecap. The fourth story titled A Roadmap for Impact Investment In India’ was authored by Vineet Rai, Founder, The Aavishkaar Group. The fifth story titled ‘Overlooked area for Impact: Last Mile connectivity was authored by Vineeth Menon, AVP, Intellecap and the sixth story titled ‘How big data can optimise the Microfinance sector’ was authored by Manoj Nambiar, MD, Arohan. The seventh article was written by Stefanie Bauer , Director, Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) Intellecap and Divya Jagasia, Senior Associate Intellecap which was about ‘Is the Indian textile and apparel industry reinventing itself ?’

Titled ‘A ‘Phygital’ model to enable rural banking’ the article from Intellecap Financial Services team, talks about how physical models have not worked in rural banking due to high costs and how India’s rural customers are not yet ready to go completely digital financially. The authors talk about the need for a disruption model that unifies both, or a phygital partnership and could address real pain points of rural customers.

The authors state that rural Banking hasn’t worked in India, just like it hasn’t in the other emerging countries. To decipher this, they dissected the rural ecosystem into three major segments: The male-dominated agricultural value chains; women-dominated allied activities such as dairy, poultry, food processing etc.; and the micro-retailing ecosystem. While micro-finance has served women credit needs to some extent, the agri and micro-retailing value chains have been majorly dependent on the informal money lenders. Despite being better served, the authors opine that, rural women are mostly unbanked, with low formal savings due to inconvenience in visiting remote bank branches, usually 5-10 km out of their localities, along with loss of a day of productive work.

The authors on to say, that about 56 percent of the Indian rural economy comprises small and marginal farmers, who cannot access credit due to fluctuating incomes, farming cycle to EMI cycle misalignment and agricultural uncertainties. Village level micro-enterprises also struggle due to dominance of cash transactions, limited credit history and insufficient financial documents. From a financial institution (FI)’s perspective, high cost of acquisition, constant service support coupled with in-sufficient credit history accentuates the overall complexity in underwriting these segments. Limited experience of micro FI (MFIs) to underwrite individual loans has impeded the graduation of JLG customers to larger ticket individual loans. For micro-retailers, the lack of financial access constrains their SKU holding power and turnover. Consequently, for distributors, this blocks working capital, constraining their growth.

The authors say that while the Banking Correspondent (BC) model, long considered a potential solution for the rural banking ecosystem, has met with moderate success. Low commission rates prevent BC operations from becoming a primary income source for the BC household. Moreover, the enormous pain points of cash management make the success of the model is dependent on merchants with high liquidity.

Moreover New-age Small Finance Banks and Payment Banks have been unsuccessful in fully leveraging the opportunity to offer better banking services to rural customers. Banking licenses were offered to MFIs and other institutions with the hope that these institutions will be able to serve rural customers with holistic solutions, and at the same time, digitise re-payments to improve their own margins. However, the deposit ticket size challenges fixate banks’ focus on non-rural / NTB customer segments through separate banking verticals.

The author go on to state that Phygitisation of the rural ecosystem, is a potential solution to enable rural banking.

Here’s why:

The author highlights that globally, such partnership models and digital data usage have already been tried with success stories in Africa and China. The Jaza Dukka model of micro-retailer digitisation covers 17,000 kirana stores. It has resulted in 20 percent growth in inventory and sales. In China, the TaoBao platform hosts more than 5 million businesses, across 2000+ villages. The data trail generated from the use of platform has allowed banks to provide unsecured loans without financial statements or prior credit history.

On a final note that authors state that clearly, physical models have not worked in rural banking in the past, due to the cost structures involved and the Indian rural customer is not ready for going completely digital just yet. They stress the need of a disruption model that unifies collaborations through value propositions for both FIs and customers. A phygital model based on unique partnership between Banking, MFI, FMCG, and agricultural sector players provides the needed consolidation and solutions that address the real paint points of the rural customers.

Aavishkaar Group to catapult into Asia, Africa with latest capital infusion

Mumbai, 14th October, 2019: In a significant coverage to the Aavishkaar Group post the US 37 Million (INR 260 crores) investment by Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank, Business Standard featured us in a detailed story titled, “Aavishkaar Group to catapult into Asia, Africa with latest capital infusion”.. The story written by Senior Journalist Anjuli Bhargava, talks about how with this infusion Group Founder and Chairman Vineet Rai attempts to make the next leap as the largest impact platform in the two continents.

The detailed article talks about the Aavishkaar Group which today has assets under management of Rs 6,700 crore. With the investment from FMO, Vineet shares how this latest infusion of capital will be used to catapult the impact fund business into a platform for impact investment in Asia and Africa, increase associates stake, capitalise the debt businesses and will help bring in the latest technology and best talent to grow the company.

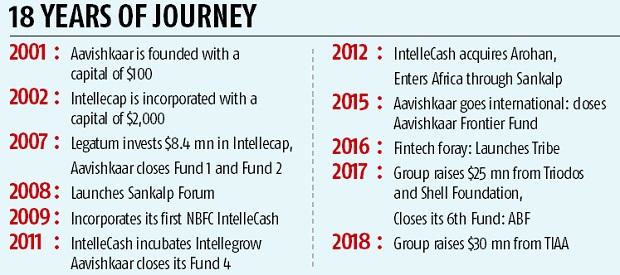

The journalist opines that to understand the leap that Vineet Rai is attempting to make, one needs to go back in time. The edifice on which the group stands today came up in 2001 with an investment of a mere $100. The company was incorporated based on the belief that if the capital is handed over to the right talent, it can solve many of the problems that low-income communities face.

In 2002, a second block was added to Aavishkaar. If those who have previously not been entrepreneurs have to turn entrepreneurial, they need someone to advise them. Intellecap, the advisory arm of the group, was added to the stable with a capital base of $2,000. The thinking was that you needed intellectual capital as well as financial capital to grow a business.

The business grew and, by 2007, Aavishkaar Capital had closed two of its funds (money was raised to be invested in social enterprises) and begun investing. In 2007, Dubai-based Legatum took a stake in Intellecap with an investment of just over $8 million. At the time, around 2006-08, micro finance itself was in its early stages and social impact companies were virtually unknown in the Indian landscape.

To grow, these companies needed both equity and debt funding. Intellegrow was incubated under the Intellecap umbrella to provide debt lending to small and medium enterprises.

Meanwhile, the group also acquired Kolkata-based Arohan (the NBFC crisis had happened and Arohan was sinking like many others) to provide equity funds to SMEs and subsequently retail micro finance. The gambit worked. Arohan’s Assets Under Management (AUM) has risen from Rs 28 crore at the time of acquisition to Rs 4,800 crore in seven years.

In 2008, aware that few understood the impact eco-system or what it was attempting, the group launched the Sankalp forum to bring together the world’s most promising entrepreneurs, most committed investors, policy makers, government officials, and others under one roof at least once a year.

By 2012, Aavishkaar felt ready to take its Sankalp forum to Nairobi in Africa, another emerging destination for impact finance. “At the time, impact investing was still an alien animal. Advocacy and a deeper understanding of the impact sector was and still is necessary for the space to thrive,” said Vineet.

Three years later, after having raised and invested four funds in social enterprises in India, the group raised the Aavishkaar Frontier fund of $48 million for investment in nine companies in Bangladesh, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. This was the first foray out of Indian shores.

More recently, the group has identified a new yawning gap and launched a fin-tech product – TRIBE – that uses technology to offer small loans to businesses in the informal segment. In general, micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are not catered to by banks due to the small size of their requirements, the banks’ limited ability to reach them and unproven credit history. Using technology, TRIBE reaches these tiny enterprises, offers them loans of the sizes they require, and collect enough data to assess their credit worthiness. “This helps us take credit calls on these enterprises,” explained Anurag Agrawal, Group Chief Operating Officer. Technology is also used to stay connected with the borrowers and to collect payments when due.

The author goes on to say that while Vineet and others argue that the MSME space is severely underfunded, Micro finance loans currently in India are in the range of Rs 2 lakh crore (lent by all MFIs in India) while it is estimated that the MSME market is ten times the size of the micro finance market but the penetration is currently one tenth. In other words, the upside for anyone who gets the model right is staggering. As a regional platform, the group is hoping to offer the full range of services that any enterprise focused on solving development issues might require.

Through Aavishkaar Capital, equity finance can be provided; Arohan (one of the fasting growing verticals) can offer micro loans of any amount; Intellecap can act as an advisor and provide intellectual capital to the enterprise; Sankalp brings all stakeholders together.

What gave the group the confidence to position itself as a regional platform arose from two factors. One, its business grew by leaps and bounds. While the group’s credit-based AUM rose from Rs 234 crore in FY14 to Rs 4,500 crore by FY19, its fee-based business rose from Rs 983 crore to Rs 2,200 crore in the same period. As of now, total AUM is roughly $1 billion. They hope to grow this to $7 billion by 2025.

Two, Aavishkaar was able to prove its basic premise to a large extent: companies can actually solve larger social problems while making money, one of the most controversial aspects of impact investing. The funds have been invested in over 60 companies, primarily in India. The 30-odd exits have resulted in returns of 3.7 times the capital invested. “We have been able to validate that the impact space works on commercial principles,” said Agrawal.

Three investments have been made in the platform as of now. In 2017, the group raised $25 million from Triodos and the Shell foundation. In 2018, it raised a further $33 million through TIAA, the world’s third largest pension fund, again at the holding company level. The latest investment of $37 million has taken Rai and his team and associates’ share in the group down to just over 51 per cent.

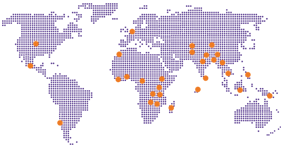

“My focus is on scale for now and this latest investment by FMO gives us the opportunity to walk on that path,” said Vineet. From a vision perspective, he says the group wants to work in Asia, Africa and Latin America, although it is yet to make any inroad into Latin America. For expansion into Africa, a team of 25 is now based there. In Indonesia and Bangladesh, it so far only has a few investment managers.

The question the impact sector is asking whether an impact investor can metamorphose itself into a platform for the region, straddling two continents. Sceptics argue that impact and all private equity investment is based on very deep embedded knowledge of the local environment and factors at play.

To invest in an enterprise in another country is one thing but having the local expertise to advise, guide and counsel social enterprises in an environment hitherto alien is easier said than done. So, Aavishkaar has taken on a big challenge. How far it manages to deliver is yet to be seen.

Reports & Policies

Our Impact Map

Sign up for our newsletter

© Copyright 2018 Intellecap Advisory Services Pvt. Ltd. - All Rights Reserved