A Smart and Resilient City Go Hand in Hand

Initially announced in 2014, the US$1.2 billion Smart Cities Initiative is still being actively negotiated, but there is clear momentum to bring this 100 cities effort into reality in the coming months. Without a doubt, it is critical that urban issues capture sufficient attention in a rapidly changing India. Those thinking about India’s cities have been watching closely to see how and where this new agenda will unfold. The Ministry of Urban Development released a 46 page concept note that starts to map out how this initiative will be implemented and some early signs are promising. It’s encouraging, for example, that technology is emerging as only part of the scope, in addition to softer considerations.

As the agenda is further honed, it is also important to consider what we mean by smart. A smart must have the capacity to prepare for weather, but to also bounce-back from shocks and stresses. Examples from last year alone underscore this: The Guwahati landslides and floods in June; the Malin landslide in Pune in August; and Cyclone Hudhud in October. It’s not just sudden events that are affecting Indian cities and towns. Temperatures are rising, reaching more than 50 degrees in cities like Delhi and Indore. These conditions are dangerous for vulnerable groups like children and the elderly, and present a major health risk for workers in construction sites and factories that lack cooling and proper ventilation. Excessive heat can also hinder economic productivity. A study by ICRIER on the diamond cutting industry in Surat found that above certain heat and humidity thresholds, daily output drops by 2% per degree. Smart cities need to equip themselves to handle stresses that materialize slowly – such as rising temperatures and shifting disease patterns– which can paralyze economic, social, and physical systems. One way to be smart in the 21st century is to be resilient.

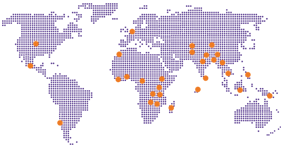

India has strong experience to shed light on what is required to build resilient cities. Through the Rockefeller Foundation pioneered Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN), more than 15 Indian cities have proactively strengthened their abilities to prepare for, respond to, and bounce back from the impacts of climate change. These cities, such as Bhubaneswar, Gorakhpur, Indore, Mysore, Shimla, and Surat, continue to develop city resilience strategies to understand how climate change affects existing challenges, including: water scarcity, poor solid waste management, and disease outbreaks. In some cases, they have started to implement measures to respond to these challenges.

There are five areas where resilience aligns with the Smart Cities Initiative:

- Decentralized systems – Even existing cities are struggling to provide basic infrastructure and services, like safe water and energy, and the number of Indian cities is expanding rapidly. By 2030, it’s projected that the urban population will climb to 590 million (up from 340 million in 2008). Climate change presents challenges to existing systems from cyclones, floods, landslides, and extreme heat. When part of a system breaks down, failures can cascade throughout multiple systems and bring about wide-spread disruptions. Cities like Indore have been experimenting with different models to promote modularity and redundancy in water service provision. Based on research by Taru Leading Edge, a conjunctive water use system has been introduced, and communities in peri-urban and underserved areas are disaggregating the sources of water for different purposes – so clean drinking water isn’t used to flush toilets – and diversifying the sources. In one poor community, the introduction of reverse osmosis water treatment has reduced the incidents of water-related disease from contaminants like e-coli. The quality of water is higher than existing sources, and for that, residents are willing to pay. Another benefit of decentralized systems is that they can promote ownership closer to where services and infrastructure are being provided. This reaps dividends when it comes to the maintenance, operations, and longer-term endurance of these systems.

- Ecosystems services – One of the by-products of India’s massive urban transition is land development of area that have provided services that protect water sources, enable flood retention, and reduce urban heat-island effects. Without foresight, growing cities may invest in development targets with more immediate financial returns at the expense of longer term gains important to health, viability, and competitiveness. Smart cities would do well to get this balance right. Gorakhpur, a city for which 25% of the land regularly experiences waterlogging – spreading disease – understands the need to reduce stagnant water. For the past couple years, the Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (GEAG) has been working with government and community stakeholders to promote climate resilient agriculture in peri-urban zones. The results so far have included increased flood buffering capacities, as well as the conservation of water retention systems. The introduction of climate sensitive practices has also yielded direct benefits for families that rely on agriculture by improving farm productivity and annual income, and by providing greater livelihood security.

- Learning – A city cannot be smart unless it is equipped to adapt and integrate lessons from past experience into new policies and practices. Cities need to be poised to handle uncertainty.

- Coordination – A smart and resilient city coordinates across government departments, scales, and sectors, connecting with relevant city stakeholder groups, including civil society, business, and research and technical institutions. Surat has done this successfully, with a focus on flood early warning. In 2013, Surat’s end-to-end early warning system helped avert a major crisis that could have been on par with the 2006 flood that resulted in US$4.5 billion in damages, and left much of the city underwater for almost a week. While coordination is benefited by better projections of rainfall and water levels, it’s the softer qualities, like stronger relationships, trust and information spreading that have been most path-breaking. This system requires sharing information and making decisions amongst a national agency, state authority, municipality, and wards within the city. Effective coordination can also yield better economic value by designing investments that tick multiple boxes.

- Public participation – There is no silver bullet that can produce a resilient city. The impacts of shocks and stresses land unevenly on residents and sectors depending on geography, socio-economic status, education, demographics, and a host of other factors. For these reasons, it’s impossible to generate a truly smart and resilient city without processes that meaningfully engage the full diversity of views, needs, and experiences.

The Smart Cities Initiative offers a tremendous opportunity to help Indian cities prepare for the worsening challenges posed by climate change. Embracing resiliency and learning from lessons already pioneered successfully throughout India and the region would be a step in the right direction. This strategy, which involves transparency, sharing information, and engaging all relevant stakeholders, is the best way to build truly smart cities.

About Authors:

Ashvin Dayal is an Associate Vice President and Managing Director at The Rockefeller Foundation. He manages the Foundation’s regional office based in Bangkok, Thailand, and oversees work across Asia, strengthening and complementing the Foundation’s initiatives around the globe.

Anna Brown is a Senior Associate Director at The Rockefeller Foundation, where she manages the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN). She is part of a team tasked with refining the Foundation’s global strategy and also serves as deputy manager of the Asia Regional Office.