A ‘Phygital’ model to enable rural banking: Intellecap writes for Forbes India

Aavishkaar Group’s content partnership with Forbes India, one of the most reputed business publication allows our leaders from across the Group to share their ideas, insights and expertise through this yearlong special series.

This is the eighth article as part of this partnership.

Mumbai, Nov 8, Friday: Neha Kumar, Senior Associate, Intellecap , Abhishek Shah, AVP, Intellecap and Himanshu Bansal, Former Associate Partner, Financial Services at Intellecap contributed the eighth story in the Forbes series November Issue as part of our yearlong content partnership with Forbes India.

As a quick recap the first story titled ‘Instant loans: Alternate data to drive next financial inclusion wave’ in this Forbes Series was authored by Atreya Rayaprolu, Co-Founder and CEO Tribe3. The second story titled ‘Smart villages: Driving development through entrepreneurship’ was coauthored by Santosh Kumar Singh, Director, Intellecap and Ankit Gupta, Manager, Intellecap. The third story titled ‘What most women-led enterprises in India have in common’ was coauthored by Urvashi Devidayal, Sankalp Lead India and Prachi Maheshwari, Gender Lead Intellecap. The fourth story titled A Roadmap for Impact Investment In India’ was authored by Vineet Rai, Founder, The Aavishkaar Group. The fifth story titled ‘Overlooked area for Impact: Last Mile connectivity was authored by Vineeth Menon, AVP, Intellecap and the sixth story titled ‘How big data can optimise the Microfinance sector’ was authored by Manoj Nambiar, MD, Arohan. The seventh article was written by Stefanie Bauer , Director, Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) Intellecap and Divya Jagasia, Senior Associate Intellecap which was about ‘Is the Indian textile and apparel industry reinventing itself ?’

Titled ‘A ‘Phygital’ model to enable rural banking’ the article from Intellecap Financial Services team, talks about how physical models have not worked in rural banking due to high costs and how India’s rural customers are not yet ready to go completely digital financially. The authors talk about the need for a disruption model that unifies both, or a phygital partnership and could address real pain points of rural customers.

The authors state that rural Banking hasn’t worked in India, just like it hasn’t in the other emerging countries. To decipher this, they dissected the rural ecosystem into three major segments: The male-dominated agricultural value chains; women-dominated allied activities such as dairy, poultry, food processing etc.; and the micro-retailing ecosystem. While micro-finance has served women credit needs to some extent, the agri and micro-retailing value chains have been majorly dependent on the informal money lenders. Despite being better served, the authors opine that, rural women are mostly unbanked, with low formal savings due to inconvenience in visiting remote bank branches, usually 5-10 km out of their localities, along with loss of a day of productive work.

The authors on to say, that about 56 percent of the Indian rural economy comprises small and marginal farmers, who cannot access credit due to fluctuating incomes, farming cycle to EMI cycle misalignment and agricultural uncertainties. Village level micro-enterprises also struggle due to dominance of cash transactions, limited credit history and insufficient financial documents. From a financial institution (FI)’s perspective, high cost of acquisition, constant service support coupled with in-sufficient credit history accentuates the overall complexity in underwriting these segments. Limited experience of micro FI (MFIs) to underwrite individual loans has impeded the graduation of JLG customers to larger ticket individual loans. For micro-retailers, the lack of financial access constrains their SKU holding power and turnover. Consequently, for distributors, this blocks working capital, constraining their growth.

The authors say that while the Banking Correspondent (BC) model, long considered a potential solution for the rural banking ecosystem, has met with moderate success. Low commission rates prevent BC operations from becoming a primary income source for the BC household. Moreover, the enormous pain points of cash management make the success of the model is dependent on merchants with high liquidity.

Moreover New-age Small Finance Banks and Payment Banks have been unsuccessful in fully leveraging the opportunity to offer better banking services to rural customers. Banking licenses were offered to MFIs and other institutions with the hope that these institutions will be able to serve rural customers with holistic solutions, and at the same time, digitise re-payments to improve their own margins. However, the deposit ticket size challenges fixate banks’ focus on non-rural / NTB customer segments through separate banking verticals.

The author go on to state that Phygitisation of the rural ecosystem, is a potential solution to enable rural banking.

Here’s why:

- Cash income is the primary reason for account dormancy and rural cash economy. By digitising the income for the farmers, as well as their business expenses, FIs can look to drive account primacy, which in turn encourages banking behaviour. Partnerships with aggregators such as FPOs, co-operatives etc. or digital agri platforms can facilitate the effort.

- Liquidity of the digital money earned, through trusted entities, is vital to build a sustainable solution. On-boarding trusted value chain players as BCs can drive liquidity of the digital money and allow people to transact frequently. Through this, savings also get a much needed push and travelling to a physical branch is no longer required. Cash can be withdrawn in bite sizes, while the rest is saved automatically. Innovative goal oriented ‘gold savings’ or ‘Diwali savings’ products that leverage local customs and aspirations of rural consumers, can further promote digital savings.

- Phygitisation of the kirana value chain through FMCG/OEM partnerships and enabling digital payments at the merchants, through USSD or a merchant assisted model, can help complete the digital loop, and also enable access to credit for merchants. Retailers can also double up as BCs, adding to their existing incomes. The digital trail capacitates working capital (WC) finance to retailers, thereby improving SKU holding power and turnover.

- The phygital ecosystem data trail can enable access to finance for all key stakeholders. Products such as cattle finance, WC finance and equipment finance can be offered through data-driven scorecard tools created by the banking / MFI players, leading the value chain digitisation effort. Partnership with equipment OEMs can also drive loans against the (semi- perfect) collateral by enabling interest subvention and promoting secondary market for collateral under a buy-back agreement.

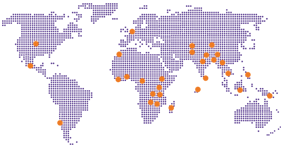

The author highlights that globally, such partnership models and digital data usage have already been tried with success stories in Africa and China. The Jaza Dukka model of micro-retailer digitisation covers 17,000 kirana stores. It has resulted in 20 percent growth in inventory and sales. In China, the TaoBao platform hosts more than 5 million businesses, across 2000+ villages. The data trail generated from the use of platform has allowed banks to provide unsecured loans without financial statements or prior credit history.

On a final note that authors state that clearly, physical models have not worked in rural banking in the past, due to the cost structures involved and the Indian rural customer is not ready for going completely digital just yet. They stress the need of a disruption model that unifies collaborations through value propositions for both FIs and customers. A phygital model based on unique partnership between Banking, MFI, FMCG, and agricultural sector players provides the needed consolidation and solutions that address the real paint points of the rural customers.

View full article